An Empty Seat at the Table

As I sit before a newly clean table, I find I can breathe a bit easier than I could before. Not that the table is entirely clean (I think that would be nearly impossible in this apartment): My partner's computer and a couple of his books linger there, beside a grinder. This is, has always been, his table and will forever be happy to hold his things. I have my desk. I don’t like things to be on coffee tables. But this is the main table in our apartment, and has, for years, been dirty. Dinner plates would find crevices between piles of weed, old mail, a computer, an ipad, and a nearly toppling pile of books. But now that it is clean I am inclined to consider the table. Because sometimes you don’t see something until it is in a different light: here, the pale reflection of the light outside on this surface is like a moon in the living room.

A dear childhood friend visits me from the west coast and we talk about the fact that I am changing jobs, going freelance, whatever that means, becoming the writer that I always wanted to be (it feels silly even to say this), but she described the writing as a center from which everything webs out. In this way writing is like a piece of furniture, a table, to be specific, which holds certain ideas and ways of being on it. I think of The Idiot by Elif Batuman, in it, of course, our lost character is not found by the end, “I still had the old idea of being a writer, but that was being, not doing. I didn’t know what I was supposed to do.” It’s like putting a table in the middle of a room and saying nothing should go on it. Saying you're a writer is saying you're a table for words. In some cultures tables were made for words. The etymology of the word table is slab: that's it, they’re fundamentally, sacredly, empty.

As I consider tables, I can’t help but think about the men in my life, how my grandfather and I played gin rummy together, and then once he put his hands to his eyes and began to cry. Tables full and tables empty, tables of pesach and christmas dinner. Tables in my mind are places for families and agreements and talking, always talking. One man or another was always at the head: my grandfathers, my uncles, assuming that singular chair of the front.

One of the strangest, but surprisingly genuine gifts I ever received was a table. I lived for three years in a basement apartment with a cat and a roommate who changed each year: one, two, three, leaving behind a small token, a napkin, a fork, a tiny picture holder in their wake. The kitchen was a hexagonal space that looked out over the trash outside. It was not unbeauitful. The brick of the building as it curled around the courtyard and faced back to us, was an earthy red. I tied a cat tree up in such a hazardous fashion it could never be used, then, a couple of years later, I took it down and replaced it with two pictures of Leonardo DiCaprio that were exactly the same right next to each other: double Leo. Once the ceiling fell onto this very floor. But that was all after my boyfriend-at-the-time, came in with my gift. It was a table top. He had adhered white tiles around blue ones in diamond patterns. I remember helping him put the fine pale birch legs on because I was better at drilling than he was. He never grouted the tiles and broke up with me within six months of making me the table. But I kept it there until I moved out, like a promise, like someday he would come back, back to our table which kept insisting on its own beauty because it was handmade. This is the pull of handmade objects. The lessons of their own making are woven into the grooves, so imperfect and full of life. You can’t hold a handmade object without feeling the - for lack of a better word - soul of of the person who wrought it. That’s why I kept the table, kept it clean, with nothing but its prisms, so that it might breathe.

I even had another table in the apartment, one that was not a coffee table, like this one. But I never used it. This one I bent over like each thing I did on the table was a prayer to an altar. I kept it clean because the tiles were ungrouted and I was heartbroken.

There were many tables before this: a giant table, too big to reach across, which was made in and too big to leave the apartment I lived in in Bushwick. This table feels stuck in time: made for the specific people who congregated around it and no one else. It came up and down with the group of friends and acquaintances who lived in the apartment. Beer bottle and lighter castles were built on it.

Pretty much anything sexual on or related to a table it hot to me. Is this some sort of symbolic incestious fantasy? I don’t think so, but if it was, according to some psychoanalyst I would probably be in the company of kings. What matters here is the table. When I think about why, I realize that a table is a structure of power. As I mentioned earlier, it’s a place where agreements are made, where friends, and families gather, and where there is a certain amount of social decency (forks on the left for example, and watch your throat, if your neighbor’s knife is facing toward you in a dinner setting.) The inversion of the table is where we get into the kinky, all that is not “seen” by society. Including being paid ‘under the table’, or the hands or feet communicating with one another in jolts and grazes like animals.

I think of Judy Chicago’s table, and what it so long meant to have a seat at a table. To sit at a table, which is what one usually does, the table is the node of connection, whose architecture highlights the head, chest and arms, all functions of communication and outward expression. Of language. In The Dinner Party Chicago inverts this, by adding vulvic patterning to the plates, bringing out from the darkness the divine feminine, and names of the goddesses and women who must not be forgotten. The triangular shape of the table is significant in that it does not have a head. The respected guests would sit at the table in a varied arrangement of closeness and distance. There is no hierarchy, but there is an almost elliptical distance from one guest to another: first close, and then far away.

Judy Chicago 1974–1979, The Dinner Party

Tables quarter a space on the longitudinal and latitudinal lines, there is a space above and below a table, and there is the space around and on the table. However a person or thing is in relation to a table is a highly significant stance. As a mind experiment, imagine, as quickly as you can, a small story that goes with each of these tabular positions:

someone stands at a table

sits at a table

stands on a table

goes under a table

walks around a table

leaves a table.

A chair is empty at a table

Each act is extremely symbolically potent. A story forms directly from that stance.

And when someone rises from a table the power dynamics immediately shift on account of the dramatic spatial dimension by people seated on chairs. The table also acts as a pseudo stage in front of which people can stand to deliver a message, on top of which can present objects, people, or nothing but a thick air.

King Arthur’s knights were of the round table, and while their quest, of course, was a physical journey, their origin is implicit in their name, as if their brotherhood is solidified by the table’s shape. Here the table is round, at term now popularly co opted by the ‘think pieces’ and NPR-style ‘round table’ discussions that can become spirals, but their aim of course begins with the shape of this piece of furniture as an emblem of the equality of each person, seated in their personal and collective power. In the illumination of King Arthur with his knights, the holy grail levitates at the center in a Judy Chicagoan vulvic shape. So the attendants are equal, and the divine feminine is present as form of connection: love shared between them, and abundant nourishment.

A 1470 reproduction of Évrard d'Espinques's illumination of the Prose Lancelot, showing King Arthur presiding at the Round Table with his Knights

For many years I used stools as small moving tables in apartments that kept shifting and roommates and general unease meant I would findreasons for sitting in different places and bring the small table to me. Tables are quite ancient inventions, used in ancient China, tables were mainly for writing and painting. The oldest table was discovered in ancient Egypt and was simply for “keeping objects off of the floor.” Ancient Greeks used tables for eating, and the Romans had the Mesa Luna, which I’m assuming translates roughly to the meal moon. But I didn’t look it up, and I could be wrong. Either way, there is something quite moonlike to the table. Usually it functions throughout the day, getting filled and emptying with whatever is being used on it. It reflects the activity it serves, because it is changing it is fallible, there is a point of softness to the existence of a table, a silence that can easily be ruptured. Meet enough times at a table over the course of years and you’ll find that you can go back in time and live out memories at these tables from before.

During the Black Death in Europe, nobles started eating in the parlor on account of relative social isolation, and these rooms became known as dining rooms, and the concept of who eats with the family, hence, who a family is was greatly cut down from the large halls reminiscent of tribal gatherings.

We live in a humble one bedroom apartment in Brooklyn. It takes thirty seconds to walk from one side of it to the other: end to snail-shaped end. Here we have a total of ten operating tables, each of which has an extremely important role in the everyday functions of our lives and the lives of the plants that live on two of them. Some are for food preparation, some are for books or keys or altars or work, weed, and records with their record player. Then there’s the squat central coffee table, the one over which we eat and exchange words. It is as if there is, right above it, an invisible levitating crown, because all of us are drawn toward it, and it monitors the actions of the apartment. We have fought across this table. We have fallen in love again at this table. When people visit they sit here at its grimey dark wood and we offer them water.

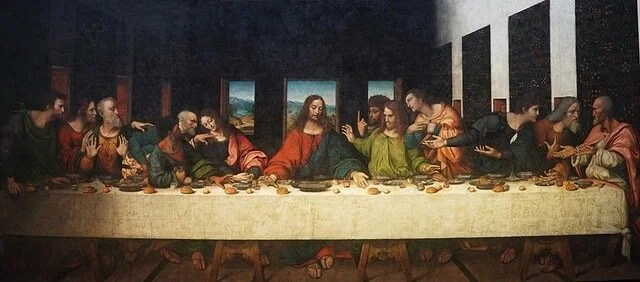

A patriarchal figure arises in my mind when I think of this archetypal table. Leonardo da Vinci and his Last Supper portrays a Jesus whose gesture directly reflects that of his positioning on the cross. His arms are extended out, in a lower position toward the food in a gesture of grace and generosity. Implicit in the act is a silence which is undisturbed by the whisperings of Jesus’ neighbors. In the malay of feet, Jesus’ are crossed.

Leonardo da Vinci The Last Supper 1495-1498

“Don’t Stop Beleivin’” plays louder and louder, pummeling through a diner in New Jersey where a crime boss sits, waiting for his family to join him. Our camera, in the last scene of The Sopranos cuts close to Tony, to his son, to Carmella, his wife. All around people are gathered or alone in their own worlds, and yet, there is a sense that someone else is coming to the table, someone who is not part of the family. Tony is seated, covering any kind of concern he might have. Like the seat created for Elijah in the Jewish tradition, the table always calls to another. A social promise whose bisecting nature, as in the life of Tony Soprano, always means there is something more. A seated person is a vulnerable, trusting person, so from anywhere, something, someone else may arrive. And all we can do is sit with the people we love, tell them we love them and ask them to hand us the pepper if we need it, believing all the while that we are among friends because have all agreed to sit here together. Or maybe we are the ones who are watching, what would we, as the outside, as the underside, as the unseen, bring to the table?

writing is labor!

if you like what you read you can tip me on venmo: Irene-Lee-22

thanks!